The first time we see the file name “Eminence” is in Season 1, Episode 7. During the brilliantly choreographed Music Dance Experience—a spectacle of Lumon-sanctioned frivolity in celebration of Helly R. reaching the exciting milestone of 73%!—we briefly see the file on Dylan’s screen as Milcheck dances around him and the song Defiant Jazz crescendoes alongside his rage. The file gets no further screen time beyond this brief moment, and it isn’t until the teaser for Season 2 dropped that any reference is made to the term “eminence” again.

In the season 2 teaser, a classic from The Who’s archive, 1982’s "Eminence Front" plays behind Mark S as he sprints through the labyrinthine halls of the Severed Floor. Then, the song plays again at the end of Season 2, Episode 3: "Who Is Alive.” The looping synthesizer riff intro is cold and mechanical, synching with Mark’s flickering consciousnesses as Rhegabi integrates him for the first time, revealing his first memory on the Severed Floor: Petey’s voice asking “Who are you?” This curious yet persistent call back to this particular file name and song suggests that Eminence might be more than just a file name, but a conceptual thread that, once pulled, reveals something crucial about the shows central premise.

Éminence Grise and the Deep Structure of Power

The phrase éminence grise originates with François Leclerc du Tremblay, the Capuchin friar and shadowy right hand of Cardinal Richelieu, who, as the King Louise XIII’s principal advisor, was the de facto ruler of France. Tremblay’s monastic order was marked by its gray robes, which contrasted dramatically with Richelieu’s own red vestments. Their political dynamic reflected this sartorial symbolism, as Tremblay was a constant shadow to Richelieu. From this dichotomy, and the honorific “Eminence” conferred on Richelieu as a cardinal, the phrase “éminence grise” (literally “gray eminence”) was derived.

While Richelieu is remembered as the face of absolutism, it was Tremblay—his advisor, strategist, and diplomatic negotiator—who embodied the machine behind the mask. Both men rose through the clerical hierarchy, but their backgrounds offer a revealing contrast. Richelieu, despite noble lineage, grew up in a financially precarious household following his father’s death, and was steered toward the clergy to preserve family income. Tremblay, in contrast, was born into a well-connected and wealthy family, with a classical education and early experience in diplomacy and warfare before choosing monastic life.

These contrasting paths to power illuminate how class background, spiritual legitimacy, and institutional loyalty converged to produce a new model of governance, one reliant on both symbolic and systemic control. Richelieu wielded visible power, but it was Tremblay who crafted the ideological scaffolding that it rested upon. They pioneered techniques of centralization, bureaucratization, and ritualized obedience that presaged modern statecraft. Together, Richelieu and Tremblay were architects of what we now recognize as the modern bureaucratic state. Richelieu’s reforms consolidated royal power, reduced the autonomy of the nobility, suppressed religious opposition, expanded the reach of the central government, and fortified a network of surveillance1 and administrative control. Tremblay, through religious reform and spiritual influence, infused this machinery with a sense of divine inevitability.

Though unseen, Tremblay was instrumental in shaping ideological and strategic decisions. He embodied the concept of a shadow statesman whose hands steer power without leaving any fingerprints. He demonstrated that real power need not be visible to be vast. The term éminence grise endures as a metonym for this: a faceless authority guiding events from the shadows, enforcing ideology not by decree, but by counsel, manipulation, and influence.

This concept maps cleanly onto the internal structure of Lumon. Like Tremblay and Richelieu, Lumon’s visible hierarchy is split between figurehead and faceless functionary. The company’s shadowy “Board” never speaks directly and is mediated through proxies. Kier Eagan, mythologized into a paternal icon, is the more visible figurehead. Part Richelieu, part capitalist prophet. But the true operators, the ones who define the logic of the Lumon world, the contours of Macrodata Refinement, and the limits of Innie knowledge, remain unnamed. As with the opaque inner circles of real-world institutions and governments—defense contractors, intelligence agencies, corporate lobbying arms—Lumon simulates transparency while veiling its core functions.

The grotesque posthumous fate of Richelieu—his embalmed head stolen, exhibited, and eventually photographed—casts a haunting shadow over the idea of legacy as control. Once the most powerful man in France, Richelieu was reduced to a macabre curiosity, paraded as both spectacle and artifact. This dismemberment of power, literalized through his fragmented corpse, echoes eerily in the figure of Kier Eagan. Like Richelieu, Kier is elevated to secular sainthood within Lumon’s corporate theology, his image reproduced in paintings, rituals, and aphorisms. His myth, like Richelieu’s severed visage, is preserved, distorted, and exhibited to sanctify institutional power.

But Kier, too, is a constructed myth—his body long dead, his head metaphorically embalmed in pseudo-religious doctrine and corporate ideology, resurrected in uncanny, animatronic wax and appropriated iconography. The Eagan dynasty, like Richelieu’s legacy, persists through narrative control, severed from human frailty and repurposed to sanctify institutional power. They are not remembered as people, but as symbols—preserved, distorted, and exhibited to inspire obedience. Just as Richelieu’s mummified face once toured the salons of post-revolutionary France, Kier’s teachings are paraded through Lumon’s halls, a mask stretched over machinery, the front of an eminence long since passed into memory.

The Eagans, heirs to Lumon’s sprawling influence, are not simply wealthy—they are embodiments of hereditary control, repackaged for a technocratic era. Their power does not rely on divine right but on accumulated capital, corporate myth-making, and narrative monopoly. Like the aristocracies of 17th century France, the Eagans reproduce their rule through legacy, secrecy, and control of narrative. Their mythos becomes corporate scripture; their dynasty, a company. In this way, Severance becomes a critique of how feudal structures have mutated, surviving beneath the shiny modernity of capitalist bureaucracy, dressed in corporate attire.

The Who’s “Eminence Front”: The Spectacle and Performance of Power

The inclusion of The Who’s 1982 track "Eminence Front" over the closing credits of Season 2, Episode 3: “Who Is Alive?”—is but anything but incidental. As Mark and Rhegabi trigger his first experience of reintegration, the song’s ominous synth riff swells beneath the scene as Rhegabi asks him repeatedly what his first memory is. The scene flickers and Petey’s disembodied voice asks Mark, “Who are you?”

Written by Pete Townshend during a period of personal crisis, in which he was confronting the spectacle of rock stardom, celebrity indulgence and self-destructive excess. It is a song about glittering surfaces, beautiful facades, and the desperate maintenance of an illusion. Its recurring motifs of speedboats, endless parties and forgetful people, paint a scene of opulence and reflects a culture obsessed with spectacle, ignoring the violent structures looming underneath. But the chorus interrupts these vignettes with a reminder:

“People forget…they’re hiding.”

On its face, “Eminence Front” can be read as an auto-biographical critique of performative affluence and hollow excess, emerging at the tail end of the so called “Me” Decade. The 1970’s had been an era of neoliberal ascendency and cultural narcissism in the West, with Reagan and Thatcher reshaping the state into a vehicle for corporate power under the guise of market freedom. Globally, there was an atmosphere of political conflict and social unrest.

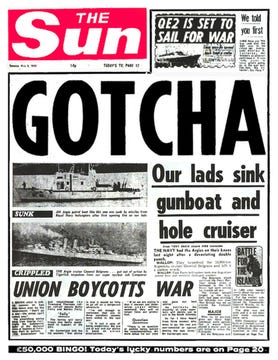

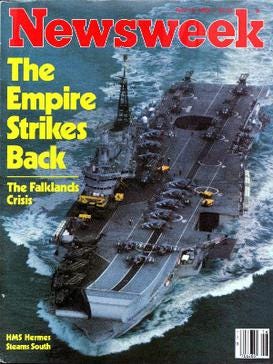

On April 2, 1982, as The Who were recording “Eminence Front” in their studio outside of London, Argentina launched an invasion and occupation of a long disputed group of islands in the South Atlantic. This embroiled the UK in what became known as the Falklands War; a ten-week, undeclared but symbolically potent conflict between Britain and Argentina that claimed the lives of over 900 people. While seemingly remote, the war had massive domestic and cultural implications in the UK, and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher seized upon the moment to galvanize nationalism and distract from severe economic strife. The successful conclusion of the war catapulted her to a landslide reelection, empowering her to accelerate the privatization and austerity that would come to define Thatcherism in the aftermath.

In this light, the Falklands War becomes an example of another historical eminence front—a manufactured crisis that allowed Thatcher to reposition herself as a wartime leader. It was spectacle weaponized to suppress domestic dissent and galvanize nationalism. A controlled conflict, waged not just for territory, but to consolidate ideology. This aligns directly with Guy Debord's theory in The Society of the Spectacle, in which Debord writes, "The spectacle is a permanent opium war waged to make people identify goods with commodities and satisfaction with survival." The Falklands war was a truly Debordian spectacle—public sentiment engineered through the choreography of nationalist imagery and military assertion.

The Who’s “Eminence Front” comments directly on this historical backdrop and critiques exactly this type of public deception. The speedboats and flying spray represent not just hedonism, but distraction, a society anesthetized by power’s performance. The song doesn’t just reflect the illusions of celebrity culture; it is a broader attack on the cultural front that masks state and economic violence and the conditioning of public perception through illusion and repetition.

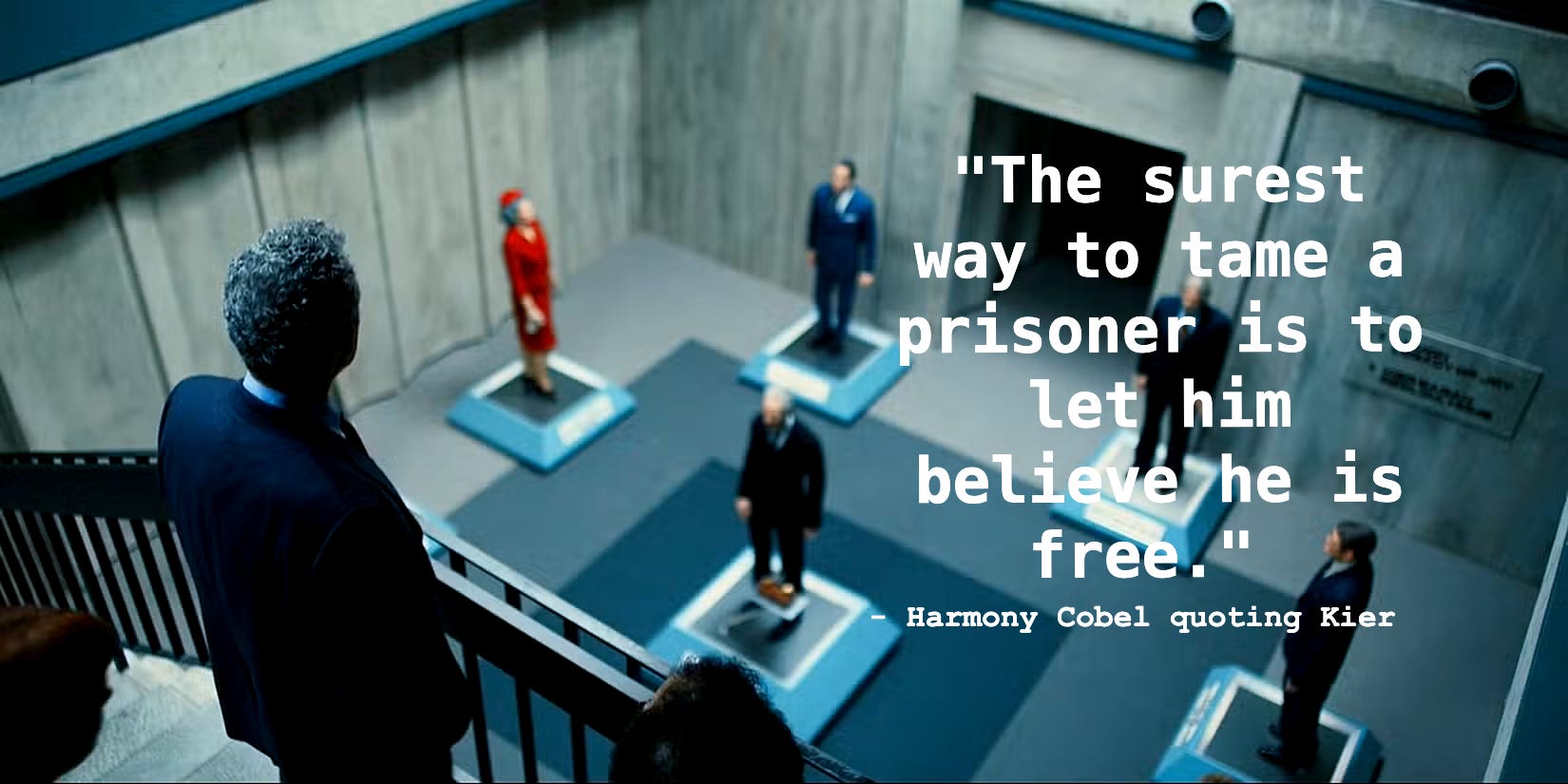

The recurrence of “Eminence”—as a file name, a song, and a symbol—reveals a throughline in Severance: the world we see is not the world that governs us. Behind every figurehead stands an architect, behind every ideology, an author. The show's deployment of “Eminence Front” is not merely atmospheric; it is a thesis statement. It exposes the artifice of control, the polished front masking systemic violence, the theater of benevolence obscuring the mechanics of domination.

Just as François Leclerc du Tremblay orchestrated policy from behind Richelieu’s scarlet robes, and just as Thatcher leveraged war to fortify neoliberal power, Lumon operates not through its visible faces but through faceless forces—ideological, algorithmic, bureaucratic. Kier is a ghostly patriarch whose teachings are manipulated into spiritual doctrine. The Board remains unseen, their will translated through sanitized corporate rituals. Macrodata Refinement itself, with its absurd and opaque task of sorting numbers by “scary feeling,” allegorizes the dehumanizing abstraction of labor under technocapitalism.

In this way, Severance becomes not just a satire of corporate culture, but a philosophical inquiry into the nature of power and the ideology of control. It interrogates the structures that condition our desires, erase our agency, and sever us—from each other, from memory, from meaning. “Eminence” is not just a file; it is a warning. An elegy for the self we lose in service of systems we do not understand, an a reminder of the illusion we mistake for freedom. And “Eminence Front”—repeating like a reminder across the series—reminds us that what we see is almost always a façade. The real decisions happen in the gray rooms, in the back channels, in the silence behind the spectacle.

As viewers, we are left with a question the show asks over and over again: Who are you? But perhaps a more urgent one echoes louder: Who decides who you get to be?

Richeleiu was also known to be fond of using a cardan grille, a technique of creating a null cipher to encrypt messages.

Another superb post. I can tell you love this show very much as do I. I can't get it out of my head. I am grateful for your clever historical/ art posts because I am getting a real education! Wanted to also "yes and" by adding that Pete Townsend/The Who also wrote and performed the song "Who Are You" which as you point out is the central question of the production. Also - I will offer the following (albeit clunky low brow) contribution - There are tons of references to 1970s/1980s movies in Severances as well as pop songs of the era - as you post out. Goofy to bring this up but...the super cheesy movie version of Alexander Dumas' The Three Musketeers (1973) and the even cheesier sequel The Four Musketeers: The Revenge of Milady - one of the baddies is Cardinal Richelieu played by Charlton Heston - and the other baddy Milady de Winter (Faye Dunaway) may be referenced in Severance via the Milady/ Milord exchange between Mark and Devon is S1E1. Also the main Severance theme includes the melodic allusion to Mission Impossible's theme written by Lalo Shifrin who also wrote the soundtrack to these goofy Musketeers films. There is also quite a bit of Lalo Shifrin's work (or nods to his work) in the Severance soundtrack - The Cat big band version - and other Bossa Nova style themes.

Also did you notice that - in the Exhalted Victory of Cold Harbor - Helly / Helena appears herself "exhaled" front and center on the top of the waterfall. She also appears as Helly to the left of Mark and as shadow-Helly to the right of Mark. 3 versions/personas of Helena - while Gemma only appears once in her Miss Casey persona. Anyway. Lots of random thoughts. I love your posts!