The Art on the Cart: Aesthetic Control and the Theft of Reality in Severance

Forbidden Love, Propaganda and the Aura of Alienation

About 41 minutes into Season 1, Episode 4 of Severance (“The You You Are”), we are given a quietly charged scene between Burt and Irving, in which they walk together through the immaculately white corridors of the Severed floor. Burt is pushing a wheeled cart, on which two framed paintings are haphazardly stacked.

These paintings flash across the screen, a brief visual anomaly, never discussed or revisited. They lack the omnipresent figure of Kier that dominates Lumon’s internal visual mythology, so it is unclear where/what they are intended for. We know that everything on the Severed Floor is strictly controlled, from the color scheme of the Innie’s outfits to the flow of information on and off the floor. And yet here they are: two iconic paintings, stripped of their context, deposited without explanation into the sterile and carefully curated visual environment of the Severed Floor.

So, what in the name of Kier are they doing there?

The first, leaning in the foreground, is Max Slevogt’s Don Juan’s Encounter With The Stony Guest (1896). In this early example of his work, Slevogt, a pioneer of the German Impressionists, captures the visceral climax of a centuries old morality tale. Behind this, partly obscured, is Aurora Borealis (1865) by Fredric Edwin Church, a titan of the American Romanticism movement and the Hudson River School. Both appear to be originals. And, let’s be honest, the Egan’s do not seem like the sort of people to have reproductions in their collection…at least not when it comes to art.

In real-world terms, these are works of enormous cultural and economic value. Church’s companion piece, The Icebergs1 sold for $2.5 million in 1979. Slevogt’s lithographs can fetch upward of $11,000. One can only imagine the price tag on an early oil painting such as this one. These are monumentally significant pieces of both American and German art, created by incredibly important artists, not just in their home countries, or even the time periods in which they worked, but in the international art movements that they helped to define. These are works that currently exist in national museums and the art collections of the .01%—yet here they are, being casually wheeled through a psychological prison by the lead of the in-house propaganda team.

These are not corporate-branded motivational posters, nor are they meaningless filler—this is Severance, after all, where nothing is incidental. So why these specific pieces? And why this specific scene? What are Don Juan and Aurora Borealis doing in Lumon’s inner sanctum?

Burt Goodman isn’t just ferrying a multi-million dollar art heist—he’s pushing around symbolic payload: a nesting-doll of visual metaphor, historical critique, and emotional foreshadowing.

The Stone Guest: Punishment, Romance and Propaganda

The first painting, leaning in the foreground, is Max Slevogt’s Don Juan’s Encounter with the Stony Guest (ca. 1906), a fevered, Impressionist rendering of the climactic moment of reckoning within a centuries old morality play. This particular example of Slevogt’s early work is inspired by Mozart’s operatic adaptation of Don Giovanni.2 The full title, Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni, literally: The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni, underscores the moral undercurrent of the tale.

The story is a tale of hubris, hedonism, and moral reckoning. Don Giovanni, a charismatic libertine, kills the father of a noblewoman he seduced. Later, he mockingly invites the statue of that man—the Commendatore—to dinner. To his surprise, the statue accepts with a nod of its head. In the opera’s climax, Don Giovanni dines with the stone effigy, who then takes his hand and drags him to hell. The Opera itself is based on a 1630’s play attributed to Tirso de Molina, entitled The Trickster of Seville3 and the Stone Guest. This play is, in turn, based on the centuries-old Spanish legend of Don Juan. This nesting-doll narrative (legend → play → opera → painting) reflects Severance’s own layered deceptions.

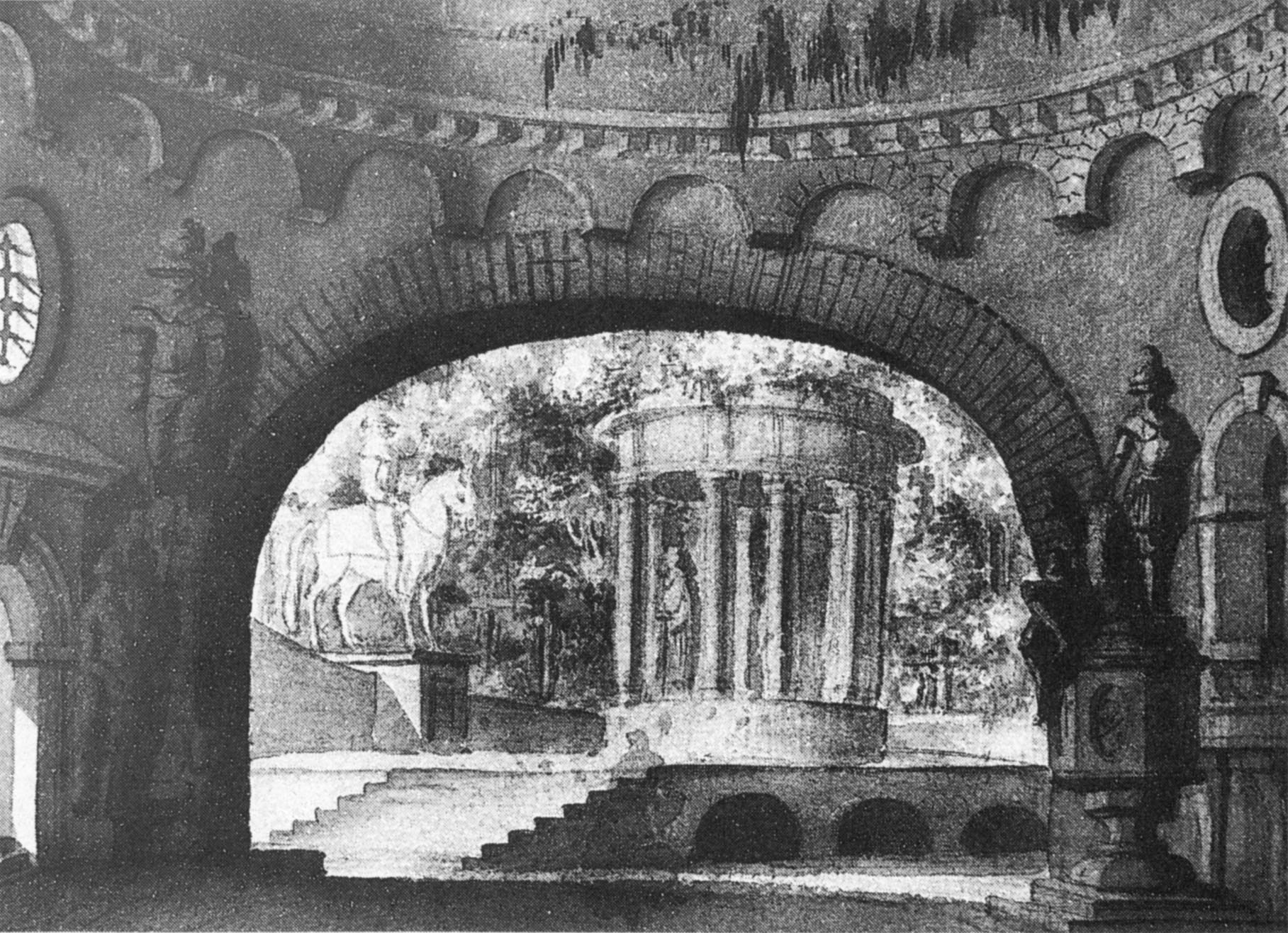

Mozart’s Don Giovanni is widely considered to be one of the greatest operas of all time, and Slevogt seemed to agree. He designed the scenery for its debut at the Dresdner State Opera in 1924, and attended performances almost obsessively. He ultimately produced a series of three finished portraits of the character of the Commendatore in that climactic moment. Slevogt’s portrayal is visceral and moralized, a reckoning rendered in brutal brushstrokes and colors that smolder like coals.

The painting’s operatic lineage and its violent climax echo the psychological intensity of Severance’s narrative arc. When given historical and artistic context, it functions as tragic for shading for Burt and Irving’s doomed romance and possible betrayal. Their layered reality, divided identities, and emotional dissonance mirror the themes of deception and punishment at the heart of the Don Juan mythos.

The Grim Barbarity of Corporate Mythmaking

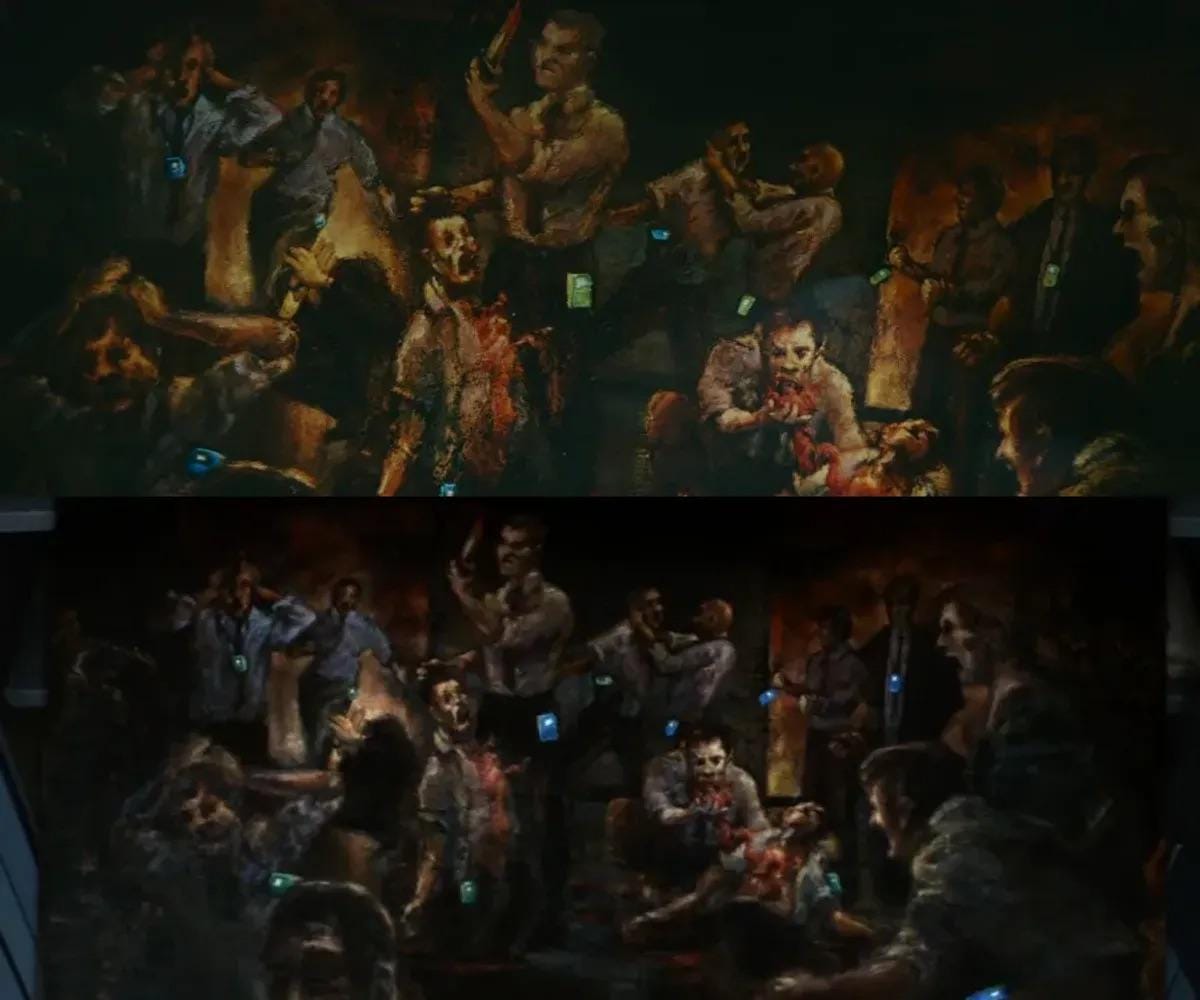

The significance of this painting deepens further in the very next episode—not just narratively, but visually—when Lumon unveils its own twisted homage to Slevogt’s style: “The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design” and its inverted twin, “The Macrodata Refinement Calamity” (Season 1, Episode 5: The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design).

These violent, absurd tableaux mirror Slevogt’s visceral visual style; clamoring figures, brutal violence, the aesthetics of destruction and retribution. They serve as corporate fables: imagined historical betrayals used to sow division and fear, to discourage fraternization between departments and encourage obedience. Milchick’s deployment of the prints—and Cobel’s approval of his “266”4 protocol—reveals how deeply entrenched this practice is, and that art’s function here is not enlightenment, but control.

This appropriation echoes Slevogt’s own censorship history. After the outbreak of World War I, Slevogt was commissioned as an official war painter and sent to the Western Front. He was expected to produce the sort of triumphant scenes of valor conducive to morale-raising propaganda; depicting the pageantry of military and the honor of German soldiers in service of their country. Instead, he produced a portfolio of twenty-one lithographs, entitled “Visions, from 1916-17.”5 These ghostly sketches were in stark contrast to his earlier work, and they painted a bleak condemnation of war. Depicting the grief, fear and destruction it wrought, as well as a deep contempt for those who fomented it. This act of resistance earned him condemnation and his work was heavily censored.

This aesthetic recontextualization is not neutral—it is a subtle yet potent form of control. Lumon’s appropriation of his anti-propaganda aesthetic as propaganda reenacts this historical erasure, and completes the suppression he resisted. By stripping these artworks of their historical, political and aesthetic contexts, Lumon participates in what Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, calls the destruction of the artwork’s “aura.” For Benjamin, the aura is not just a piece of artworks originality—it is the works embeddedness in time, place, ritual, and presence. When art is removed from those conditions and contexts, and it is re-situated for exhibition or manipulation, its meaning is transformed. It becomes disconnected from its capacity to inspire critique or contemplation. Severed from history, just as Lumon’s workers are severed from memory, it becomes a hollow spectacle.

This “spectacle” is discussed in Guy Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle”6 as not merely a media phenomenon, but the dominant mode of perception and control in capitalist society. For Debord, the spectacle is the system by which social relations are mediated through images. It absorbs all resistance, turning dissent into aesthetics, experience into simulation, and identity into brand. Lumon’s aesthetic controls of space, memory and affect is not just a quirk of corporate overreach—it is a perfected microcosm of the spectacle. The severed workers are denied access to lived memory, severed from continuity, and reduced to consumers of their own commodified labor. Even the Innie’s rebellion is quickly co-opted into the company’s internal mythology.

In Debord’s view, the spectacle replaces lived experience with representation, transforming history, memory, and even rebellion into staged illusions that reinforce the status quo. Lumon’s redeployment of Slevogt’s aesthetic--as both literal artifact and visual grammar—becomes an example of what Debord warns against: a commodification of resistance, where even anti-war, anti-authoritarian expressions are neutralized and re-encoded as instruments of control. The paintings are no longer allowed to speak for themselves; instead, they are ventriloquized by the company. Just as Don Giovanni invites death into his home only to be consumed by it, Lumon invites the art into its halls only to hollow it out and wear its skin.

The same could be said of the “Grim Barbarity” paintings, which act as visual propoganda carefully designed to resemble fine art—borrowing its emotive power while subverting its intent. These corporate myths masquerade as historical memory but are, in truth, engineered simulations, designed to instill paranoia, loyalty and fear. As Benjamin notes, the mechanical reproduction of art, and its use outside of ritual, severs it from its aura—its uniqueness, its origin, its historical gravity. But Debord takes this one step further: this severing is not accidental—it is strategic. It is the foundation of a society where all social life is mediated by constructed appearances. In this context, Lumon doesn’t just use art; it re-stages reality itself, replacing the messiness of human experience with a curated, consumable, controllable version.

According to Debord, the spectacle is “not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.” In other words, it is not the paintings themselves that matter, but what their placement, presentation, and dislocation signify both within Severance, and Lumon’s orchestrated worlds.

In this way, the cart of paintings becomes a metaphor for the spectacle itself: images emptied of their origin, context, and critique, repurposed for containment rather than expression. By inserting these historically grounded, emotionally charged works into a sterile and corporatized environment, Lumon preforms a quiet sleight of hand—it preserves the image, but nullifies its meaning. It creates a simulacrum of depth, one that gestures toward art’s capacity to critique, to awaken, to resist, while ensuring those capacities remain safely defanged.

Irving, for his part, senses this dissonance. His Innie is drawn to art, to the tactile presence of it, even as he cannot fully name why. His obsessive sketching of Burt, his attraction to Burt’s artistic space and work, his visceral reaction to the “Grim Barbarity” painting—all of this points to an unconscious yearning for the real, for the unsanitized, unmediated experience denied him by the sterile spectacle of Lumon’s world. In this way, he becomes a kind of tragic Benaminian figure—haunted by the aura of a world he cannot access, trapped in a hall of mirrors where every truth is reproduced but never revealed.

And so, Burt’s cart becomes more than a narrative anomaly—it becomes a moving reliquary, a wheeled symbol of how power aestheticizes, sterilizes, and weaponizes culture. These are not simply paintings; they are spoils of war, visual trophies looted from the domain of meaning and redeployed in the service of obedience. They are the very definition of Debord’s spectacle: a past reconfigured as image, an experience pre digested for mass consumption, an artistic act hollowed into performance.

Severance’s genius lies in the subtextual ruptures—brief flashes where the illusion falters, and deeper truths briefly shine through. But as Benjamin warns, unless we critically engage with these ruptures, they risk becoming just another layer in the spectacle—a curated anomaly mistaken for resistance, a painting mistaken for truth.

Part 2 - A Stolen Sky: Auroras, Luminism and the Art of Extraction

But Don Juan is only the first of the anomalous, aura-less artworks on the cart.

Behind him, barely visible, leans a second image—one that haunts not through reckoning, but through reverie. Frederic Edwin Church’s Aurora Borealis shimmers at the edge of he frame like a half-remembered dream. It’s muted palette and sweeping vista evoking a very different kind of reading: one that gestures toward sublime awe, historical dislocation and the colonial gaze embedded in the visual culture of American Romanticism.

These two paintings, juxtaposed and jostled on the same cart, perform a shared function: they illustrate the aesthetic arsenal of control. In this light, the pairing of the paintings is not incidental, but dialectical. While Don Juan confronts the moral consequence of hubris, the polar vastness of Aurora Borealis renders the idealogical landscapes of empire and conquest, refracted through the icy lens of imperial fantasy.

We’ve followed Burt and Irving past the Stone Guest. Now, let’s follow them into the Aurora’s chilling light to examine how Lumon’s visual regime doesn’t just control behavior, but colonizes imagination itself. We’ll trace how Church’s mythic landscape, born from 19th-century American expansionism and Protestant futurism, and becomes a proxy for the ideological question Lumon offers us: what does it mean to dream of the sky from within a prison of someone else’s stars?

I swear I’m not going to start ranting about icebergs again. You can read my thoughts on them over here.

The full title, Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni, literally: The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni, underscores the moral undercurrent of the tale.

Its relevance is slyly underlined later (S01E09 - The We We Are) when Irving’s Outie, questioned by Milchick, claims to have been home all night, watching “The Barber of Seville” (also called The Useless Precaution)—another opera about love, deception and thwarted control. Even severed, Irving’s subconscious resonates with tales of manipulated realities.

Creator Dan Erikson has claimed “266” was the number of his childhood Boy Scout troupe, but, curiously, it is also the number of a failed bill, introduced to the US Senate in 2005/2006 during the 109th Congress by Senator Frank Lautenberg. It was commonly referred to as the “Stop Government Propaganda Act,” and it aimed to address concerns about executive agencies using taxpayer funds for what was perceived as domestic propaganda. This bill arose in the wake of several controversies regarding instances where government agencies were accused of producing “covert propaganda” or “fake news” stories that were then disseminated to the American public without clear identification of their government origin. Ultimately, the bill passed in the Senate and was referred to the House, but did not become law.

But sure, Dan. Your Boy Scout troupe number.

https://www.germanexpressionismleicester.org/leicesters-collection/artists-and-artworks/max-slevogt/

https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/benjamin.pdf